Scene 2

IV - Saracura

Saracura -

Luciana Araújo

I'm Luciana Araújo, I'm a journalist, I've lived in Bixiga since 2007, December 2007. I've been an activist in the Unified Black Movement and the March of Black Women of São Paulo and, since 2022, in Mobiliza Saracura Vai-Vai, which here in the neighborhood seeks to rescue the memory that this was a territory that had as its first population nucleus a rebellious black population resistant to enslavement, but rescuing memory very much from the perspective that memory for us is future, very much linked to guaranteeing the right to continue in this territory.

Can I go on? Is everything all right there? What, did something happen? No, just the sound of the rain, but everything's fine.

Because... The two great hallmarks of Bixiga, in my opinion, are precisely a community way of life that has a lot to do with the perspective that in African philosophy, the philosophy of our original continent, speaks a lot about how ‘we are because our surroundings are’.

It's completely opposite to the Western point-of-view that ‘I recognize myself based on my differences with others’. So I think this is a very important characteristic that hasn't yet been removed from the neighborhood. And the other characteristic is exactly the conflict with this, which is a history of violent evictions of poor and black people.

From the erasure of a quilombo that already had some degree of study in the fields of recognized sciences within the university, the dissemination in journalism of documents from the City Council that referred to this quilombo, in the neighbourhood that became known internationally as the Italian quarter, through a process that is very emblematic of a whitening project led by the Brazilian state, which intended to exterminate us.Today, since 2022, we have been fighting for the preservation of the Quilombo archaeological site, and if we look backwards and forwards, the symbol of the mobilization is the Sankofa, the idea of drinking from the past to build the future, and the idea that memory is the future.

That quilombola population, the original one, the quilombo in the strict sense of the concept that we were taught in schools, a first important wave of expulsion there is directly marked with one of the main signs of the so-called development of the city, which was the construction of 9 de Julho avenue, when the flow from Paulista avenue began to descend into the central region, there was a hole in the woods, there was nothing there, and from the moment 9 de Julho was built, there are records of this, including official documentary photos from the City Museum, photos from the Museum of the Faculty of Public Health, because the discourse was always a hygienist-sanitarist discourse.

Let's develop, put an end to the polluted riverbank where the poor and blacks gather. And then you have a succession of episodes that it's scandalous that aren't more prominent in the daily experience of what is known about Bixiga, because then you have the process of widening Rui Barbosa Street, that abolitionist who had the abolition documents burned to ensure that no one asked for compensation, in this process you have a new wave of evictions, then you have the process, still in the 1950s, of both the first widening of Rui Barbosa and the construction of the Japurá building, opposite to the Town Hall, which was one of the largest tenements in the region, and at the time one of the largest tenements in the city of São Paulo.

Then there was the process of opening the Radial ring road, from 23rd Street to Jandaia Street, which also led to a series of evictions and violent removals, and which later went down in history with the revitalization of the so-called Arcos do Jânio (Jânio's Arches). Then, again, you have the Vila Itororó process, which ironically became a reference center for racial equality after more than 70 families, most of them black, were removed to build a cultural center. Then there was the removal process in the Conde de São Joaquim area, which gave rise to two CDHUs (government-funded low-income housing), one facing the other, and which, despite being projects for the low-income population, didn't even cover all the people who had been removed from the tenements and boarding houses they had on that street, for various reasons of not fitting the criteria required to enter CDHU financing.

In the 1970s, I forgot to mention, when the Minhocão was built, tearing the neighborhood in two. Vai-vai itself lost its first headquarters on July 14 street, and several members and people were removed from Bixiga during that period, giving rise to what is now the neighborhood of Cidade Tiradentes (in the city outskirts, east zone).

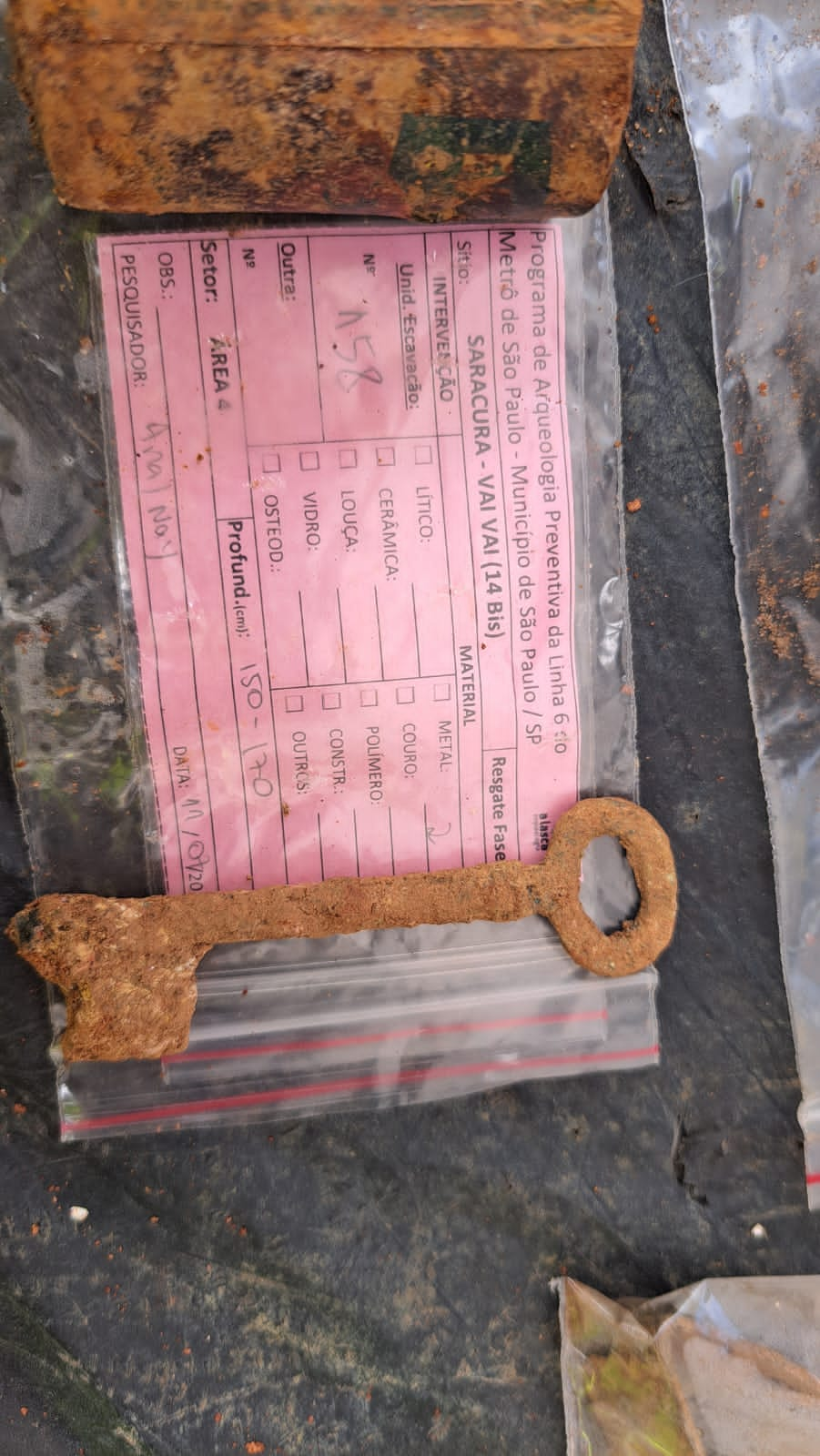

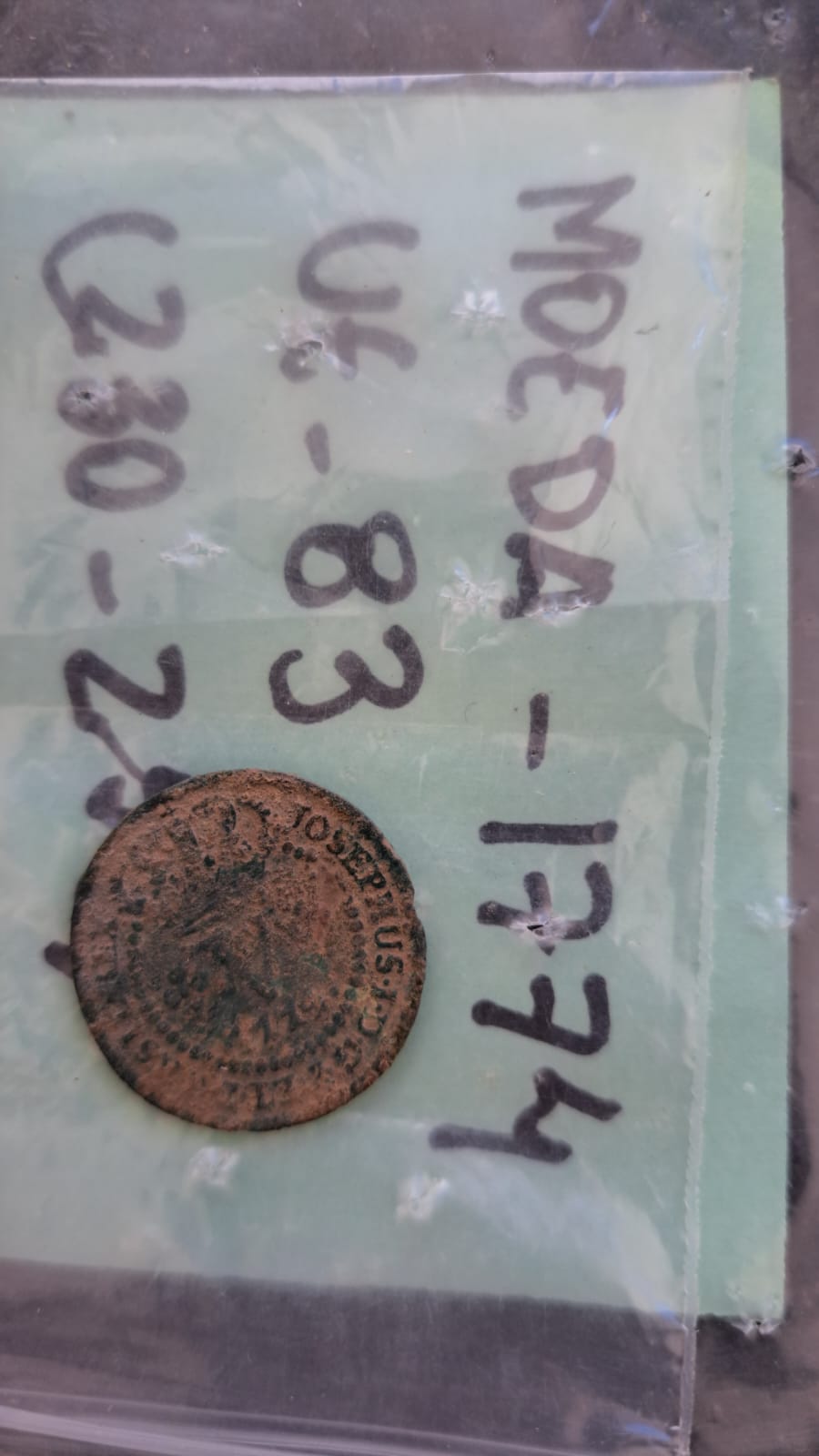

And now, finally, there's this process of excavating the subway, which has led to the discovery of an archaeological site that my personal assessment is that was only publicized because it reached us, and not for us as individuals, but for the community, because…

It's important to note that the discovery of the site was not officially publicized until an archaeologist mentioned in the research was notified that his work had been mentioned in the research and made the gesture of looking for people who live in Bixiga and work on racial issues.

And he said, “Are you aware that they've found a quilombo site in Bixiga? And we weren't. And this process was very interesting, because the day the news arrived was the day Walter Taverna died. So we were a bit... You can't go out on the day of the death of such an important and beloved figure in the neighborhood.

So we talked to some of our closest friends, but that's only when we get together to talk. That was a Sunday, June 8th. And we talked about it here and there, and we set up a meeting for Monday the 13th, a week later. In a week... This meeting brought together more than 60 people, various organizations and institutions that work in the neighborhood, that work in the black movement, here or not, nationally, the Catholic Church, the Afro Pastoral of the Catholic Church, the Povo de Santo (candomble practitioners), and it also shows how much, although institutionally and formally, the state tries to erase the black aspect and history of the trace all the time, how much it is latent in its own process of everyday ways of life, we talk about it a lot, right?

You're in the city center, but you have very strong community relations. You have a series of festivities that are festivities built from inside, not that official thing that comes and limits people to go as guests, many festivities with a conscious community perspective and you have a concentration of black institutions that once existed here that many people don't even know about.

Even the current resistance to real state speculation advance that is trying to destroy and tear down not all the old properties, but those where people still live in collective housing and which also have this perspective of building collective sociability and which is, once again, treated in a hygienist way to exchange a collective dwelling in a small room for a 19-square-meter studio to be sold for half a million.

The difference is whether you're in a community, if you're with poor black people, or if you have someone who can pay half a million to stay in an Airbnb for the weekend.

It's very connected and that's why, for us, memory is so much the future.